-

Demonstration of Authority

Since 1977 when I declared my belief in Bahá’u’lláh as the Prophet for this age and committed to abide by His teachings as best I could, the Bahá’í Faith became my spiritual motherlode. My acknowledgement of the authority Bahá’u’lláh carries as the manifestation of the Creator of the universe in this day prompts me to immerse myself in His teachings and ongoing guidance from the Bahá’í institutions He spawned. Following the spiritual path unfolding before me endows me with an inner sense of purpose that makes every day an adventure in learning more about myself, my relationship to the whole of creation, and what I need to address in myself to be of better service in this world and better prepare for the next.

No matter how formidable the task in front of me at the moment, my continual inquiry into the deeper meaning, significance, and nuance behind the spiritual principles which undergird the Bahá’í Faith grants me access to a higher authority. In effect, this bolsters my authority—and the voice, presence, and passion that come with it—such that I can put my learning into action and make a positive difference in meeting the challenges at hand.

Beginning with the The Báb and Bahá’u’lláh, followed by Bahá’u’lláh’s son, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, then Shoghi Effendi, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s grandson, and now the Universal House of Justice, the flow of spiritual guidance in the form of writings, messages, letters, and publications to Bahá’ís worldwide has continued unabated 1. Oftentimes, this guidance has been addressed to certain individuals or groups, regardless of their affiliation with the Bahá’í Faith, based on the impact their decisions may have on the welfare of the world. One such message, “The Promise of World Peace,” 2 written by the Universal House of Justice demonstrates the scope and degree of its spiritual authority by whom this body addressees—the peoples of the world. It was the first time the Universal House of Justice exercised its divinely ordained mandate to speak to the spiritual needs of everyone. This act together with the content of the message itself provided much needed inspiration and encouragement for me in the months ahead as I navigated the move from employee to independent consultant serving clients internationally and domestically. As such, it also represents a starting point for me now to organize and archive the boxes of papers and books coming from my amazing career that followed the paper’s publication!

- “Bahá’u’lláh and His Covenant.” The Bahá’í Faith, Bahá’í World Centre, https://www.bahai.org/beliefs/bahaullah-covenant. Accessed 22 May 2021. [return]

- The Universal House of Justice. “The Promise of World Peace.” The Bahá’í Faith, Bahá’í World Centre, Oct. 1985, https://www.bahai.org/documents/the-universal-house-of-justice/promise-world-peace. [return]

-

The Authority to Act Independently

My transition from being an employee working FOR an organization to contracting as an independent agent or consultant working WITH an organization was an exercise of personal and professional authority. My credo with clients (and colleagues) was: I belong here at this point in time to deliver my skills and insights about change management which, if applied, will benefit the organization(s) more than the cost incurred.

This statement of belief in oneself becomes a framework by which one can negotiate the terms of fair compensation for the fair value of something proposed and done. As I discovered at each stage of my career, negotiation of these terms over time marked the client’s and my progress on the change management path we traveled together. Along the way, I found spiritual principles that formed the basis for this framework and gave it sufficient fractality and flexibility to apply it in social systems of widely varied structure, scale, and personality. More importantly, it bestowed upon me a confidence—an authority—to meet the demands of the moment and prevail undeterred.

-

Riff on The Matrix

According to Dictionary.com, “matrix” means something that constitutes the place or point from which something else originates, takes form, or develops. In that sense, each of us is always in a matrix of some sort. It’s inevitable.

Matrices are complex systems bound by a handful of “rules” that define why they exist, how they function, and what type and degree of influence they have on the behavior of those who are part of them. How those rules get determined is cause for concern as expressed in this popular Urban Dictionary definition of “matrix” which reads: a term describing a controlled environment or situation in which people act or behave in ways that conform to roles pre-determined by a powerful person(s) who decides how the world is supposed to function. In reality, though, each of us has a unique sense of the matrix in which one’s life plays out. And that view is not static. Over the course of one’s lifetime, it may change multiple times. The matrix is personal.

Although each person carries an individual perspective, many can reach a mutual understanding and even agree among themselves about the “rules” of a “social matrix” they choose to cohabit. But to do so requires active participation. Accordingly, EACH has a HUMAN RIGHT to fully participate in shaping one’s social matrix yet a PERSONAL RESPONSIBILITY to advance, refine, and commit to the “rules” that bound it with those who share it.

-

A Fork in the Road-Part Three

My introduction to the labor management consulting team came through my mandatory attendance in a series of senior leadership workshops during which the team presented the change management program the company contracted them to implement. Admittedly, I came in both ignorant about the approach and skeptical that anything so soft-sounding could make a substantive difference in the lives of so many given the hard realities faced by the company. But by the end of the initial round of sessions, I came away a believer.

As the program unfolded and my involvement in it deepened, I realized that change management was the type of work I wanted to do professionally. Through the unwavering encouragement and ongoing support by members of the consulting team I pursued a “professional development” path that combined soaking up the coaching from consulting team members; gaining experience in designing change management strategies; playing various roles involved in carrying out the subsequent interventions; and even completing my undergraduate degree in Human Resources Management. My plan was to acquire and demonstrate these skills such that my value inside the company would be sufficient to underwrite my position as an internal change agent well into the future.

One acquisition later followed by new management and a different direction it became obvious that my Plan A was not viable. So, Plan B: do I accept a position in another area in an attempt to remain employed by the company despite the upheaval caused by the acquisition? Or, Plan C: do I allow myself to be swept up in the next reduction in force and pursue opportunities with organizations elsewhere that would value my new-found passion and expertise? After 15 years employed by a company that no longer existed, wounded by the processes of downsizing in every form, and severely limited in opportunities for professional growth, I ditched the fork in the road leading to more despair and embraced the one illumined by hope for a future doing what I loved somewhere, somehow.

-

Hope for the Future

Amid the death and destruction that marked the times, one consulting group came on the scene to setup an “employee involvement” 1 initiative with union leadership and company management. The intent was to alter the oftentimes contentious union-company relationship whereby the two could build a mutually beneficial future going forward.

This effort started with a joint steering committee structure consisting of membership from the union and the company. Collectively, they developed shared goals (related to the survival of both, most of all!) and modeled the kind of collaborative behavior they expected the proliferation of teams they commissioned on the shop floor to follow. By design, the cross-boundary participation from the bargaining unit, support services, and first-line supervision, area by area, would derive energy from the exchange of different views, experiences, and ideas within a formal team-building framework. Then, when applied to issues and opportunities within the purviews of the teams, would yield sufficient benefit to justify doing it.

Finally, something that offered hope for the future I could sink my teeth into. Based on my qualifications, I transferred to Human Resources as the internal consultant for change management working with the external consulting team to implement the Employee Involvement process—the fourth major career move in six years.

- Heathfield, Susan M. “What Does Employee Involvement Actually Look Like?” The Balance Careers. Accessed May 16, 2021. www.thebalancecareers.com/employee-… [return]

-

Downsizing to Prosperity

As the world of unparalleled success the company enjoyed a mere five years before continued unabated on its “fade to black” course, each wave of new management brought “help” from the outside in the form of consultants. Regardless of consulting firms they represented, their role, inevitably, was to offer advice about how to “trim fat” or more euphemistically, “rightsize” the organization on its downward trajectory. They proposed projects to cut expenses, streamline processes, and consolidate operations which, following the dictum of “cost walks on two legs,” undoubtedly resulted in reduced staffing as proof of their merit. In the face of almost certain hesitancy on the part of those responsible for the areas affected to carry out these “recommendations”, senior management contracted with consultant teams to implement the projects so the company could realize the advantages they promised and justify the expense of the consultants. Management meetings to mark progress on the projects became occasions to post the outcomes of internal “dueling contests” wherein yesterday there were two divisions with facilities, departments, and staffs; now, there is only one. Tomorrow, there may be none. The lesson learned: downsizing into prosperity is a losing strategy!

-

Surviving in Chaos

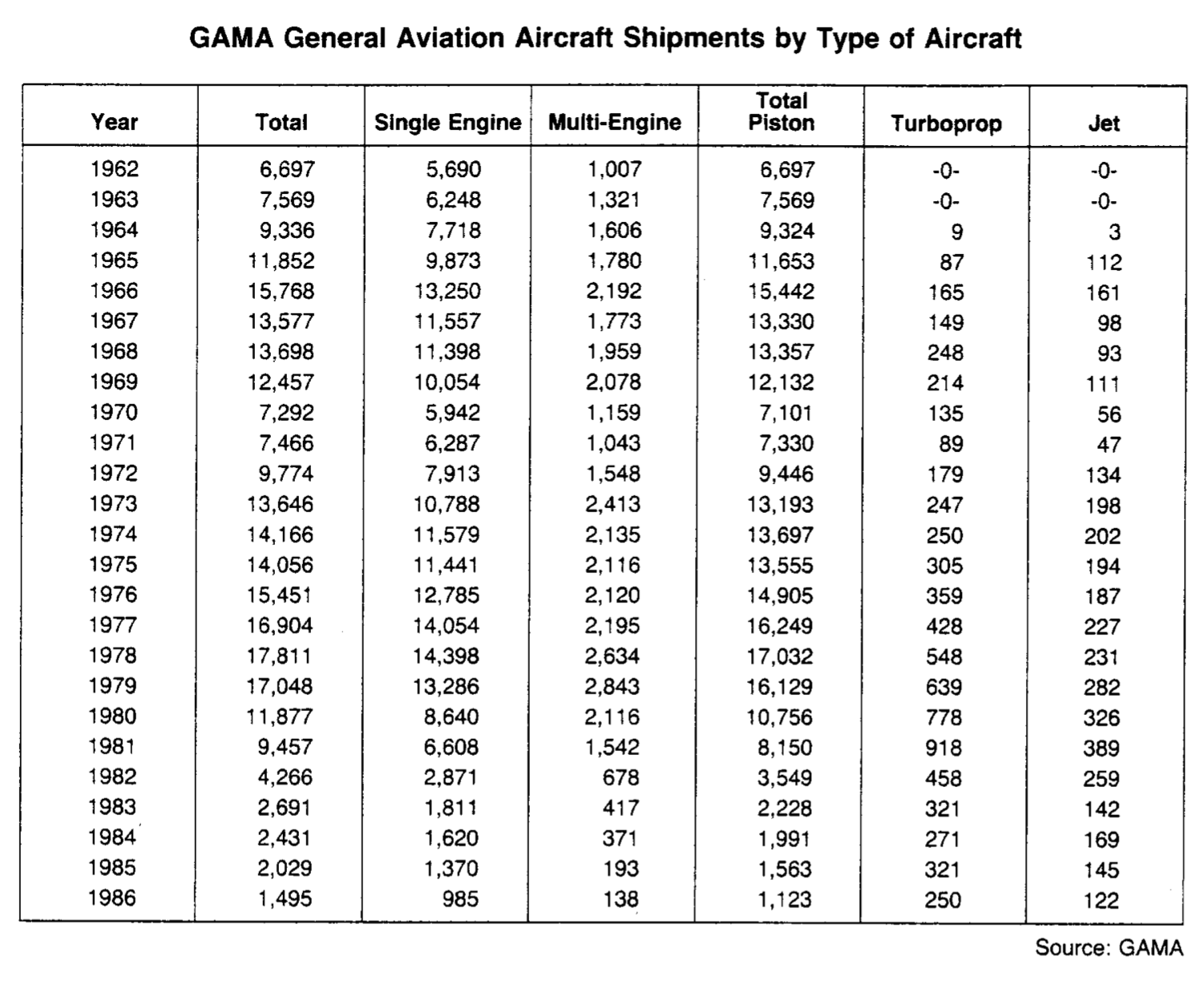

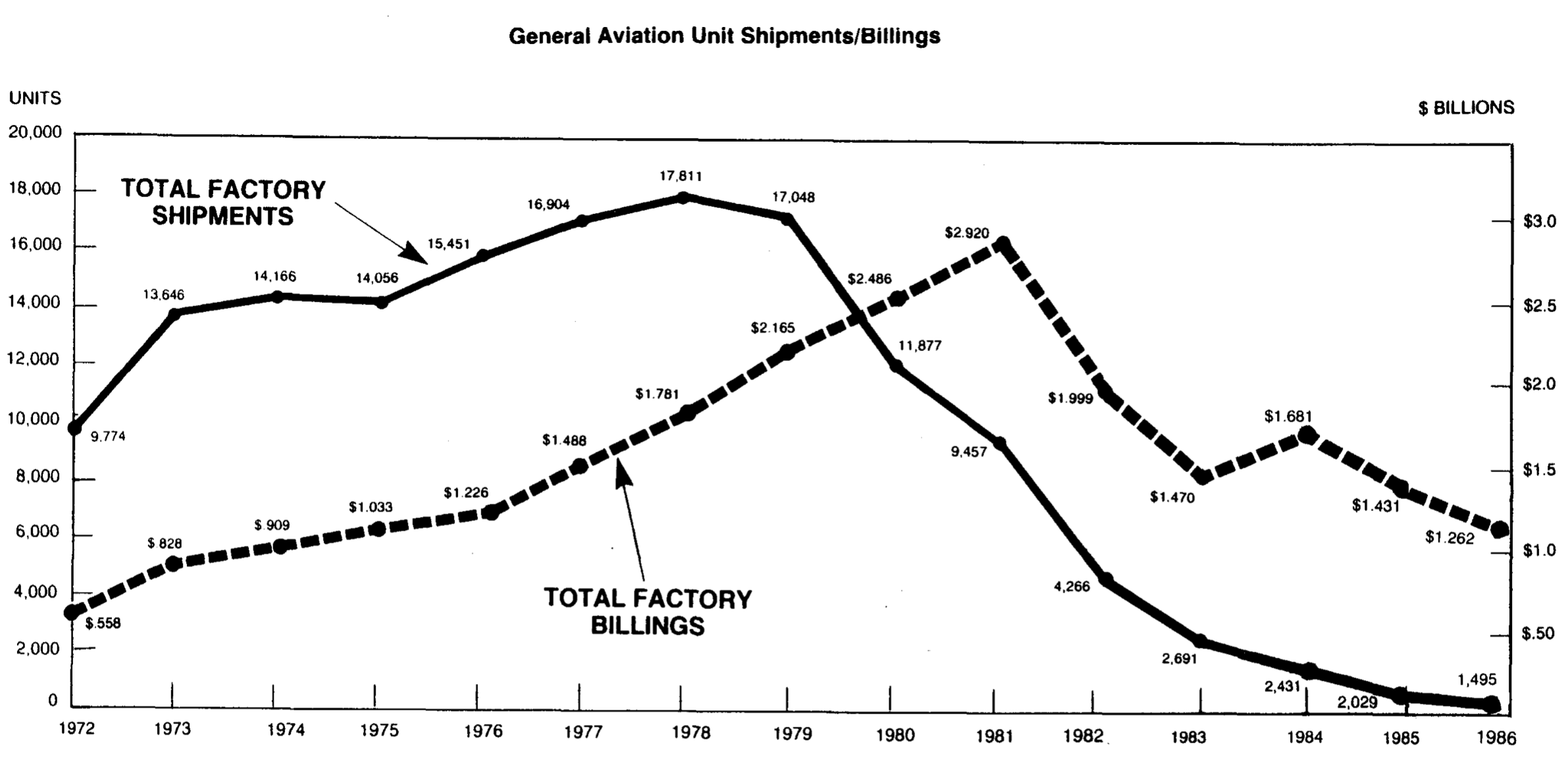

Following record-breaking delivery levels year to year in the late 1970s, the general aviation market began a sharp decline in the early 1980s and by the mid-1980s had suffered a near-total collapse.

Consequently, single-engine aircraft deliveries slowed to almost nothing and operations suffered a 75% reduction in production, people, and physical property within eight years. While hindsight points to several contributing factors, 2 skyrocketing product liability costs chief among them, annual forecasts about how bad it would get offered little indication as to the futility of initiatives to stop, much less reverse, the downturn.

Committed to “surviving in chaos,” the company adopted a culture of near-desperate experimentation with new management, new directions, new plans, new organization relationships, internally and externally—concluding with its acquisition by a deep-pocketed company in a related industry. In terms of organizational viability, this approach worked as the entity stayed afloat and continues on today.

Given the disruptive and even traumatic nature of the experience left indelible impressions on the psyches of everyone throughout the organization, it presented each with a seemingly infinite range of “forks in the road” from which to chart personal and professional paths forward. For some, those choices brought unexpected and ignominious ends to what had been successful careers. For many, the alternatives led to abrupt changes in jobs and workplaces—often to comparatively unfavorable positions—just to remain employed. But for others, the pathways opened up new opportunities that would not have existed otherwise. I was fortunate enough to encounter more promising forks in the road…and become an example of Thriving on Chaos. 3

- General Aviation Manufacturers Association (GAMA). “General Aviation Statistical Databook.” Washington, D.C., 1987, 5-6. https://gama.aero/documents/general-aviation-statistical-databook-1987-edition/. [return]

- TRUITT, LAWRENCE J., and SCOTT E. TARRY. “The Rise and Fall of General Aviation: Product Liability, Market Structure, and Technological Innovation.” Transportation Journal, vol. 34, no. 4, 1995, pp. 52–70. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20713254. Accessed 14 May 2021. [return]

- Peters, Thomas J. Thriving on Chaos: Handbook for a Management Revolution. 1st ed. New York: Knopf : Distributed by Random House, 1987. [return]

-

A Fork in the Road-Part Two

Once I took the assignment as executive assistant my relationship with the shop floor changed dramatically. I went from being a direct part of its day-to-day activities to being an interpreter of the data compiled into performance reports about what went on there. In other words, I left the “real world” of the shop floor in a physical sense and became immersed in a virtual representation of it as expressed by data generated and human behavior exhibited throughout a complex system of schedules, inventories, and procedures.

Throughout any given day, these performance reports highlighted deviations from expectations which triggered the director’s need to know what caused them, what would correct them, who was doing what by when to implement the fixes, and when would “normalcy” be restored. Beginning the first day in my new position, the director made it well-known to all that I was an extension of him. This established a new baseline for my authority which was quite different from what I carried as a first line supervisor. My duties included observing and verifying the conditions first hand that surfaced in performance reports, attending status meetings and interviewing people involved in addressing the identified issues, relaying commitments from those responsible for taking corrective actions, and following up as needed to confirm progress.

More importantly, though, my shop floor experience coupled with the director’s positioning of my role in management circles increased my authority to influence systems for production planning and production control at a division level that directly impacted shop floor performance. I could add more detail and context to the data reflected in the performance reports that, in turn, offered perspective to thorny problems and clarified priorities for departments and their functions in addressing them.

Delivering this type of contextualizing service week in and week out increased my trustworthiness among division management that I would use my presence and authority for the common good and not unfairly advantage one group or individual over another. One of the related skills I developed was how to convene management at various levels across the multitude of disciplines associated with production planning and control systems and tell stories about the conditions on the shop floor such that they understood cause and effect between the systems they represented and the real world those systems affected. Subsequently, they actively participated in proposing alternatives, developing new and modifying existing processes, and implementing projects and programs to improve overall operations.

It was on the basis of these collaborative successes that the vice-president for engineering and support services offered me a management position in his division to accelerate the rate of change within these production planning and control systems. While a definite advancement with commensurate increase in authority, taking it meant leaving the “protection” of the director responsible for production with no avenue for return should the move not work out—another fork in the road.

-

A Fork in the Road-Part One

After a year and a half in supervision, a job posting appeared for an “executive assistant” position that reported directly to the division director. Although “special assignments” may sound intriguing, because of their greater distance from daily production (more clearly an indirect cost), such projects pose a risk to one’s career unless one secures an agreement in advance about one’s destiny after completing the assignment. When these “opportunities” present themselves they constitute major forks in the road, career-wise, that one cannot revisit later and they forever alter one’s career path going forward.

Following the advise of those I trusted, I applied for the position. During my interview with the director, the question about my future and how this assignment supported it came up. I mentioned that I intended to stay with the company for the long haul and planned to complete my undergraduate degree, thereby better preparing myself for expanded responsibilities. He told me that if I postponed my college courses and applied myself to this assignment, instead, I would gain the equivalent of a PhD in manufacturing which I could leverage for advancement later on.

To further underscore his point, he took me on a walk-through of the shop floor during which he displayed his knowledge about production from design engineering to customer delivery as we passed by each work station in one product line after another. In effect, he began teaching me before he offered me the position and I started learning before I had even considered accepting it. His lesson that day went far beyond how to produce aircraft to demonstrate how to command authority from worthy character rather than hierarchical position. I was hooked. Later that week, he offered; I accepted; and just like that I left the shop floor—my life would never be the same.

-

Growing Authority on the Shop Floor

The next stage in the development of my “authority” followed with rapid promotions first to crew chief—a position covered within the bargaining unit—then to first line supervision at which point I entered into a separate contract directly with the company 1. My responsibilities changed from doing assembly line work to assigning that work to others; training them in how to do it (if required); making sure they had the parts, tools, equipment, and necessary support services necessary to do their assigned work; and, helping them resolve problems they encountered that prevented them from being successful on the job—often requiring tough decisions about the appropriate level of responsibility for the supervisor, as a representative of the employer, to take, especially when attempting to heed the call to be of service to others 2.

With the additional responsibility came a commensurate increase in authority. By being a member of management, supervising employees and their use of departmental resources to do so, added legitimacy to the exchanges I had with my counterparts in other areas. I was no longer roaming around outside my work area to simply relieve my boredom or secure what I needed to complete my own work, I carried agency that stemmed from having a purpose well beyond myself. Now, matters associated with production schedule changes, workload balancing, shortage recovery, bringing new products on the assembly line, etc. introduced me to a diverse range of actors 3 with whom our collaboration served the greater good of the company. As a result, beyond checking off the day’s activity list, I gained considerable working knowledge about how the processes of production came together to build aircraft—more granular, detailed “maps,” if you will—which would serve me well in my next step on the journey to greater authority!

- Bosserman, Steven L. “From Labor to Management.” Steve Bosserman, May 9, 2021. stevebosserman.micro.blog/2021/05/0… [return]

“Each one must be the servant of the others, thoughtful of their comfort and welfare.”

ʻAbduʼl-Bahá. The Promulgation of Universal Peace: Talks Delivered by ʻAbduʼl-Bahá during His Visit to the United States and Canada in 1912. Edited by Howard MacNutt. 2nd ed. Wilmette, Ill: Baháʼí Publishing Trust, 1982, 215. https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/abdul-baha/promulgation-universal-peace/15#814409286

[return]“The psychological self begins life as a social actor, construed in terms of performance traits and social roles.”

McAdams, Dan P. “The Psychological Self as Actor, Agent, and Author.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 8, no. 3 (May 1, 2013): 272–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612464657.

[return]

-

Planting the Seeds of Authority

In my experience, one of the by-products of assembly line work, day in and day out, was boredom. I learned to do the tasks I was responsible for then spent my time being “creative”: reading books out of sight in unmonitored restrooms and stockrooms; sneaking in moves on postal chess cards or games on boards setup in toolbox drawers; and wandering around under the pretense of seeking parts, special tools, test equipment, or inspection, expeditors, supervisors, etc. More to the point, though, I “mapped” the factory floor and noted where my work fit in the flow of operations; met with people whose work preceded or followed mine and negotiated how we could do it differently so it remained in compliance with inspection standards, but helped all of us; and learned to interpret rumors and observe how changes in production schedules and shop floor layouts in different areas indicated potential layoffs or overtime. This knowledge became seeds of my authority that would sprout and grow over time in keeping with changes in the scope of my responsibilities as well as gaining deeper insights into the dynamics of larger more complex systems.

-

From Labor to Management

The move from shop floor assembly worker to first line supervisor certainly offers opportunities for career growth, but the change in relationships with management and co-workers carries with it particular challenges that not everyone is cut out to do. I really knew nothing about supervising, in general, and certainly not with those whom had been my “comrades in arms” for seven years the day before my “promotion.”

Training was literally “on-the-job.” I did believe that “God is the helper of those souls whose aim is to serve humanity and whose efforts and endeavors are devoted to the good and betterment of all mankind.” 1 My approach to being a supervisor was to do whatever I could to help those I supervised be successful in their work. Of course, this assumed they would take responsibility to do what was within their means to handle. Most of the time they did this, but sometimes not. When they didn’t, it became my role to find out the reasons why and take appropriate action — one of the main reasons supervisors exist. Of course, many of these situations became excellent working examples of “what goes around comes around” given some of the behaviors I had exhibited towards my supervisors in times past.

“Be ye confident and steadfast; your services are confirmed by the powers of heaven, for your intentions are lofty, your purposes pure and worthy. God is the helper of those souls whose aim is to serve humanity and whose efforts and endeavors are devoted to the good and betterment of all mankind.”

ʻAbduʼl-Bahá. The Promulgation of Universal Peace: Talks Delivered by ʻAbduʼl-Bahá during His Visit to the United States and Canada in 1912. Edited by Howard MacNutt. 2nd ed. Wilmette, Ill: Baháʼí Publishing Trust, 1982, 448.https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/abdul-baha/promulgation-universal-peace/21#736903681.

[return]

-

Seeing Systems

My experiences on the shop floor in aircraft manufacturing are unique in terms of complexity of production due to imposed safety and legal regulations; complexity of aircraft itself due to interdependent systems; complexity of internal processes and procedures due to competing silos and their goals which were at cross-purposes with one another and the company overall; and, complexity of adaptability due to “Information Age” developments rapidly obsoleting entrenched industrial mindsets and inflexible organization designs.

More broadly, these experiences deepened my understanding of enmeshed manufacturing systems, the behaviors they prompted, and their consequences. I learned to see systems dynamics, sense their vulnerabilities, and ultimately, seek and find root causes of systemic problems faced by management and employees at all levels and roles in their efforts to establish, increase, or restore profitability.

It also gave me a feel for the distinctions between adhering to the letter of the law versus honoring the spirit of the law. In other words, it sharpened my skills at knowing when to follow the rules, bend the rules, break the rules, or change the rules—anticipating the consequences from each alternative, and taking responsibility for whichever choice one makes.

No doubt these proved to be useful insights to tuck into my “tool kit” as I headed closer to my future career path.

-

Independent Investigation of Truth

Among the teachings advanced by the Bahá’í Faith is independent investigation of truth. 1 Such searches, be they personal or professional, involve giving a fair hearing to compelling arguments about core principles as expressed by voices of authority. Although Thief in the Night by William Sears 2 presented an entertaining tale focused on topics I cared about, the presentation came across like a marketing ploy and lacked sufficient authenticity.

A couple of years later my curiosity led me back to those same principles this time drawn by a nagging question as to whether my “independent search for truth” would be a fair judgement without first immersing myself in their source—the words of Bahá’u’lláh Himself. After diving into several books by Baháʼuʼlláh including Epistle to the Son of the Wolf 3; Gleanings from the Writings of Baháʼuʼlláh; 4; Prayers and Meditations by Baháʼuʼlláh; 5 and The Kitáb-i-Íqán: The Book of Certitude Revealed by Bahá’u’lláh 6, giving deep consideration to the significance of His words, and engaging in numerous discussions for further clarification and perspective I could confidently say I found what I was looking for. On Naw-Rúz 1977, my 4-year, soul-searching odyssey came to a close with my declaration of faith in Baháʼuʼlláh.

Acceptance of Bahá’u’lláh and a commitment to follow His teachings transformed my view of people and the world around me. My embrace of defining principles like the oneness of the world of humanity and the existence of an attractive force called love that links us together gave me a fuller appreciation for our diversity as individuals and the value that each of us possesses as full participants in this global human family. 7

For as long as I can remember I could “mind map” dynamics among people in various social systems such as within the family, at school, in the workplace, etc. and use that insight as a survival mechanism to defend or advance myself depending on circumstances. Adopting a Bahá’í perspective was like being legally blind, donning newly-developed corrective lenses, seeing everything in a totally different way, and opening up possibilities for a future well worth the investment of my time and energy!

But how and into what do I make that investment remained unanswered…

- ʻAbduʼl-Bahá. The Promulgation of Universal Peace: Talks Delivered by ʻAbduʼl-Bahá during His Visit to the United States and Canada in 1912. Edited by Howard MacNutt. 2nd ed. Wilmette, Ill: Baháʼí Publishing Trust, 1982, 440. https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/abdul-baha/promulgation-universal-peace/32#246863996. [return]

- Sears, William B. Thief in the Night: Or, The Strange Case of the Missing Millennium. 1961. Reprint, Oxford: G. Ronald, 1981. https://archive.org/details/thiefinnightor00sear. [return]

- Baháʼuʼlláh. Epistle to the Son of the Wolf. Translated by Shoghi Effendi. Rev. ed. 1953. Reprint, Wilmette, Ill: Baháʼí Publishing Trust, 1976. https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/bahaullah/epistle-son-wolf/1#804716281. [return]

- Baháʼuʼlláh. Gleanings from the Writings of Baháʹuʹlláh. Translated by Shoghi Effendi. Rev Ed. Wilmette, Ill: Baháʼí Publishing Trust, 1952. https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/bahaullah/gleanings-writings-bahaullah/1#529444114. [return]

- Baháʼuʼlláh. Prayers and Meditations by Baháʼuʼlláh. Translated by Shoghi Effendi. 1938. Reprint, Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1974. https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/bahaullah/prayers-meditations/1#187607508. [return]

- Baháʼuʼlláh. The Kitáb-i-Íqán: The Book of Certitude Revealed by Bahá’u’lláh. Translated by Shoghi Effendi. Wilmette, Ill.: Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1950. https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/bahaullah/kitab-i-iqan/1#990539395. [return]

- ʻAbduʼl-Bahá. The Promulgation of Universal Peace: Talks Delivered by ʻAbduʼl-Bahá during His Visit to the United States and Canada in 1912. Edited by Howard MacNutt. 2nd ed. Wilmette, Ill: Baháʼí Publishing Trust, 1982, 301. https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/abdul-baha/promulgation-universal-peace/21#736903681. [return]

-

Piqued Curiosity

I became aware of the Bahá’í Faith during several animated conversations with a co-worker on an aircraft final assembly line in Wichita, KS. On the Bahá’í timeline, these exchanges occurred during the brief period between completion of the Nine Year Plan at Ridvan 1973 and the subsequent launch of the Five Year Plan at Naw-Rúz 1974.

At the time, I was 24 years old, married, two children, and less than two-years seniority in an industry notorious for its cyclical employment patterns.

I had recently enrolled in classes at Wichita State University for what would turn out to be an unsuccessful third run at getting an undergraduate degree.

A couple of years before I had read the excerpts from A Separate Reality: Further Conversations with Don Juan 1 by Carlos Castañeda in the March 1971 issue of Esquire Magazine.

This sent me on a long reading adventure into literature about and by Native Americans. It also opened up my receptivity to learn more about a panoply of religious and nonreligious belief systems. Enter the Bahá’í Faith and the book: Thief in the Night by William Sears 2

It didn’t take. But my curiosity was piqued!

- Castañeda, Carlos. A Separate Reality: Further Conversations with Don Juan. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1971. https://archive.org/details/separaterealityf00cast [return]

- Sears, William B. Thief in the Night: Or, The Strange Case of the Missing Millennium. 1961. Reprint, Oxford: G. Ronald, 1981. https://archive.org/details/thiefinnightor00sear. [return]

-

Source of Authority

During my career I had the opportunity to work with people of capacity in all types of organizations: academic institutions, business enterprises, professional societies and private foundations, government agencies, religious groups, etc. The reality is I had no certifiable credentials that qualified me for membership in any of these entities. Still, I possessed sufficient perceived value in the eyes of their leadership that they granted me access and gave me platforms to influence the design of processes and behavior of people within their purviews. The perceived benefits people within these organizations gained through my interactions with them led to long term working relationships that extended across several years and in the case of some, decades.

I’m at the stage of life where I need to sort through an over 30-year accumulation of “stuff” from my consulting practice while I’m still able. Then, I can digitize and make public what may be useful more generally and dispose of the rest so that family members won’t have to do it.

Aside from the physical aspects of cleaning up, I intend use this exercise as a prompt to take a deeper dive into the source of authority I carried that enabled me to do what I did during my career. My core assumption is that it came from my grounding in the teachings of the Bahá’í Faith. To explore this notion further, I plan to arrange my career output along a timeline that parallels the availability of publications and messages from the Universal House of Justice—“the international governing council of the Bahá’í Faith.” This post together with “The Universal House of Justice—April 30, 1963” marks the beginning of this effort.

subscribe via RSS